Cave Men: Marking the 75th anniversary of the 147th Infantry on Iwo Jima

Story by Sgt. 1st Class Joshua Mann, Ohio Army National Guard Historian

(03/21/20)

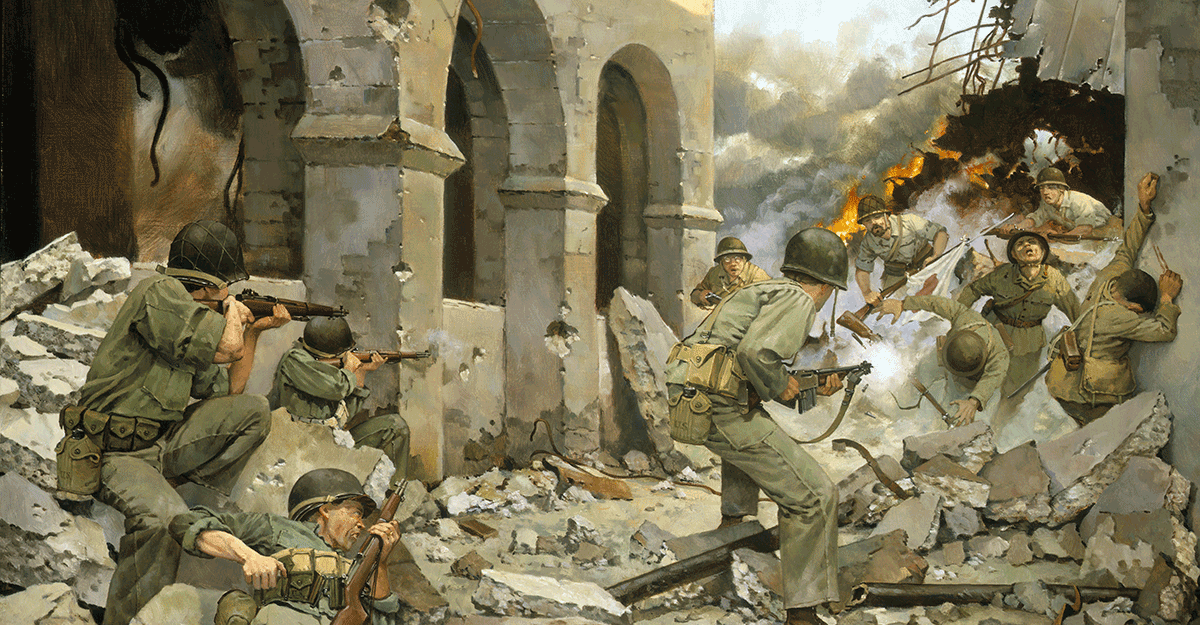

By all popular storylines, the Battle of Iwo Jima is one of the greatest and most iconic battles in U.S. Marine Corps history. From the iconic photos of Marines landing on its volcanic ash beaches on Feb. 19, 1945, to the raising of the American flag atop Mount Suribachi, Iwo Jima’s popular legend is that it was an all-Marine show. For the Soldiers of the Ohio National Guard’s 147th Infantry Regiment, who fought on the island from March to September 1945, nothing could be further from the truth.

The Cincinnati- and Southwest Ohio-based regiment entered active service in October 1940 as an element of the 37th Division. Shortly after departing for the Pacific Theater in 1942, the regiment was relieved from the Buckeye Division and remained a separate regimental combat team for the duration of the war, serving in the Composite Army-Marine (CAM) Division on Guadalcanal and as a garrison force for the Marines on Emirau Island and New Caledonia.

When the 2,952 men of the regiment landed on Iwo Jima on March 21, 1945, the sounds of battle still filled the air. The ships transporting the troops and equipment ashore made quick runs to the beach to avoid enemy observation and fire. Five days later, the Marines declared themselves victors and departed the island, leaving the mop-up operations to the 147th.

“USMC General Harry Schmidt, the V Marine Corps commander, estimated that only 100-300 Japanese remained on the island,” wrote James J. Ahern, a platoon leader in Company F, 147th Infantry. “His estimate was greatly optimistic.”

Thousands of Japanese had turned the 8 square miles of island into a series of complex underground defenses that consisted of 13 miles of sophisticated caves connected by tunnels. The enemy lived underground by day and moved about at night, securing supplies and attacking American forces. In the early morning darkness of March 26, as if to mock departing Marines, 200-300 Japanese attacked the bivouac area of a unit set to depart the island that day. The Marine Fifth Pioneer Battalion, with the help of Company A, 147th Infantry, which brought along a flamethrower tank, helped blunt the attack.

The regiment split the island into three sectors and assigned each battalion the task of clearing out the holed up enemy, one way or another. The 147th engaged in three types of actions to accomplish that task: ambush patrols, combat patrols and cave explorations.

“Our company formed teams equipped with guts, flashlights and pistols,” wrote Company B veteran James McGuire. “Our cave cleaners called themselves cave men.”

The extensive nature of the caves made elimination of the enemy extremely difficult. The 147th developed various techniques to clear the caves and maintained a rapid tempo which sought to prevent individuals and small groups of Japanese troops from banding together and carrying out large-scale attacks. Removal attempts varied from the use of small arms and hand grenades to smoke and flamethrowers. Nisei interpreters and Japanese prisoners of war were also utilized try and convince the enemy to surrender.

‘Many of the Japs were talked into surrendering, others, deeply fanatic, holed up until ferreted out and killed,” added McGuire.

Ahern noted that using cave men was dangerous, as enemy guards posted at the entrances were quick to shoot anyone attempting to enter the cave, something he experienced firsthand while closing one cave.

“I threw in a white phosphorous grenade and the Jap threw it back,” Ahern wrote. “I was slightly burned by the exploding grenade. I tossed in a fragmentation grenade and the Jap threw it back. When it exploded a fragment grazed my wrist. This got my dander up. I cleared the cave with a flamethrower.”

The cave closing techniques developed by the 147th Infantry led to the killing or capture of 2,469 enemy soldiers and continued until the end of June 1945.

“Daytime or nighttime, combat action on Iwo Jima was always exciting. The risks were there, some days were more adventurous than others,” added Ahern.

The regiment departed Iwo Jima on Sept. 8, 1945, and moved to the Island of Okinawa for similar duties. After two months of occupation duty there, the 147th Infantry returned to the U.S. and was inactivated on Christmas Day 1945 at Vancouver Barracks, Washington.

In a commendation letter from Lt. Gen. Robert C. Richardson, the commanding general of the U.S. Army Forces, Pacific Ocean Area, the regiment’s contribution was summed up well.

“(The) members of the 147th Infantry Regiment, whose mission was the destruction of the Japanese forces remaining on Iwo Jima after organized resistance had ended, displayed consistent courage and combat ingenuity in dealing with an enemy determined upon a course of fanatical resistance. Despite conditions of terrain and emplacement favorable to the Japanese, morale remained at a high level and few casualties were sustained. . . . The military proficiency and devotion to duty constantly manifested by the regiment were in great measure responsible for the final security of a vital advance base.”