Counterdrug analyst finds purpose through tragedy

Story by Sgt. 1st Class Chad Menegay, Ohio National Guard Public Affairs

CINCINNATI, Ohio (07/22/19)

She’s working through a loved one’s loss — it’s arduous and never stops. She pushes the pain aside, like rolling a boulder nearer the top of a hill only for it to roll back down. The lows return.

She thinks about her father’s drug overdose and wonders why he did these drugs, and sometimes her frustration spikes. Then it falls numb, and she’s left with childhood memories in disrepair because once they were a pair — when he took care of her and looked on her with adoring eyes — but now, because of his addiction, they are apart.

Still, she’s able to bridge the space between them because she knows he is proud of who she has become and the work she does.

Grief does not change you…

it reveals you

– John Greene

Ohio Air National Guard Tech Sgt. Chelsea Lovelace conducts counterdrug operations as a criminal analyst for the Ohio National Guard’s (OHNG) Counterdrug Task Force (CDTF). She has taken all the heartache her father’s addiction wrought on her and channeled it into preventing such a tragedy for others. Lovelace, who was a senior in high school when her father Eric died of a morphine pill overdose, helps the Cincinnati Police Department’s Narcotics Division catch and prosecute drug dealers.

“I would say that’s 90% of my job, figuring out, OK, this must be the dealer,” Lovelace said. “This must be the guy that’s selling for the dealer. The police will get tipped off by confidential informants, and we’ll roll off that like a snowball effect.”

CDTF analysts support the seizure of illegal substances. In 2018, the OHNG’s CDTF assisted law enforcement agencies across the state in the seizure of more than $120 million in property, cash and drugs.

“We’ve worked with heroin cases, fentanyl cases, cocaine, prescription opiate pills, I mean, I’ve seen every drug come through here,” Lovelace said.

Lovelace is motivated when she sees a case evolve, she said.

“We go from something like, you know a dealer’s name, but you don’t know what he looks like, and then doing intense research and putting these thousands of pieces together into something that’s big and clear and concise,” Lovelace said. “That’s rewarding for me. It’s almost like instant gratification, especially when a case is still developing, trying to put the pieces together for the officers and finding, ‘hey, he drives this car, here’s this plate. Can you tell me where he lives?’ Then, you’re searching for hours through different databases trying to paint that picture for them, and when you actually get it, it’s a rewarding feeling.”

She said she hopes she’s helping keep the drug out of someone’s hands.

“Maybe they have an intervention from their family members, and it’s one less overdose,” Lovelace said. “The more drugs you can get off the street, the more lives you’re saving.”

Lovelace, who has worked with the CDTF for three years, said she knows she’s making a difference in the community, but the job is bittersweet because of her father’s death.

“I feel like I’m definitely helping get rid of the drugs on the street, but it also does make me feel sad because I’ve lost my father to drugs,” Lovelace said. “So, I don’t know, it’s a weird feeling. I’m happy I’m making an impact, but it’s just like I wish somebody would have been there who could have made an impact on my father.”

Absence is like the sky,

spread over everything

— C.S. Lewis

“I feel like he’s always there in the back of my mind, especially when we deal with cases that involve younger guys who are just starting out in life, and especially if you find out they have kids, it hits home a little bit,” Lovelace said. “You’re thinking, ‘oh, this guy’s going to jail, you know, his kids aren’t going to have a dad, but hopefully this is a wakeup call, and he turns his life around, gets off the street and gets off drugs and just gets away from drugs entirely.’”

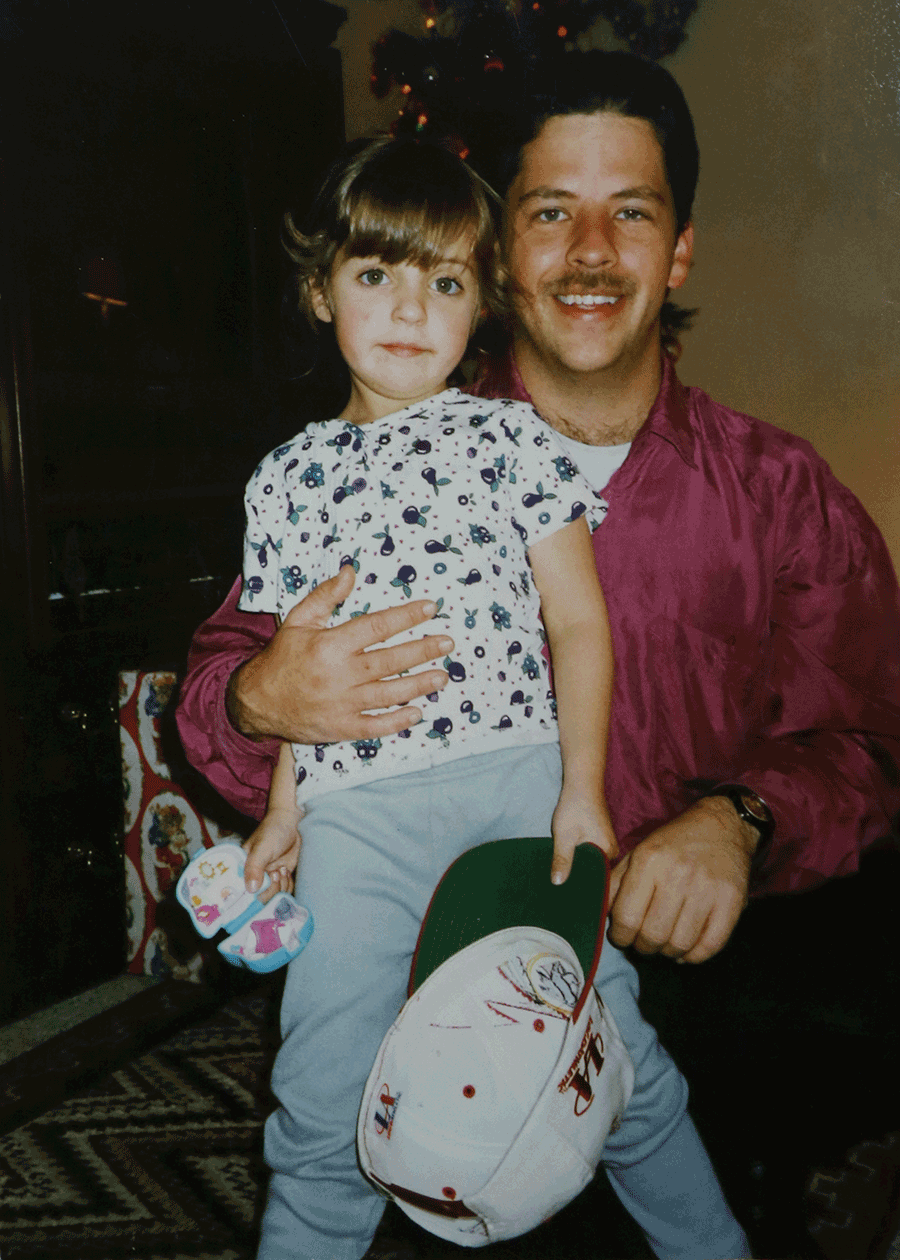

Lovelace said she and her father were close while she was growing up, despite his addiction, her parents divorcing when she was young and only seeing her father on weekends and holidays.

“I’ve noticed sometimes I’ll be out in public, and I’ll see someone who looks like him, and I’ll do a double take, and I feel my heart saying, like, ‘Oh my God, is that him?’ and then I have to realize, you know, he’s not alive,” Lovelace said.

Lovelace is still dealing with grief almost 10 years after his passing, and she says there’s some frustration and anger that goes along with it.

“I just recently bought a house, and there’s some things that I’d like to do around the house, but I’m not super handy,” she said. “He was really good at laying bricks and things like that. I look at it and I’m like ‘wow, I wish he was still here. He could have really helped me with this.’”

Lovelace said she thinks back on memories mostly around Christmas time and holidays. “I kind of relive it and think, ‘Oh, I wonder what I was doing 10 years ago today, probably hanging out with him,’” Lovelace said.

Though they were close, she said she doesn’t like to relive her childhood memories with her dad because it just makes her sad.

“I don’t like to rehash it very much,” Lovelace said. “I don’t like to think about it. It’s probably not a healthy coping mechanism. The process has definitely taken some time. It’s a lifelong battle.”

The love between father and daughter knows no distance

— unknown

“Eric was just on cloud nine when he became a father,” said Chris Lovelace, Eric’s sister and Chelsea’s aunt. “He thought the world of her and couldn’t take his eyes off of her. He loved her more than anything else in this world and, in his heart, he felt extremely close to her.”

However, it wasn’t long after Chelsea was born his drug addiction started to kick in, and it was probably the greatest cause of divorce between him and Chelsea’s mom, Chris said.

“So, he just continued down that path,” Chris said. “He would get clean, then get back on drugs.”

Chelsea said she has a memory of when she was in third or fourth grade when her father asked her to go in her mom’s medicine cabinet and get some pills for him, which she did and didn’t realize until much later what had happened. Chris said when times were really bad for Eric and he was on more drugs, he would disappear a bit from Chelsea and the rest of the family. Chelsea started putting the pieces together in junior high school.

“I remember I got in his car this one time, and it had a really bad odor to it, well, I realized that odor was marijuana,” Chelsea said. “I started putting stories together and realizing that he really did have a problem. So, younger, when I was more naïve, we had a good relationship but junior high and high school I started to pull away and not talk to him as much.”

Chelsea’s father had tried rehab a couple times, and, near the end, had just graduated a thorough program in Braddock, Pennsylvania. A pain doctor gave him morphine pills, and he accidentally overdosed, passing away Oct. 27, 2009.

“It was a few days before they found him,” Chelsea said. “It wasn’t an open-casket funeral; it was cremation.”

Chelsea said that with open-casket funerals she’s been to, she felt like it was easier because she had the chance to say goodbye.

“I never got that closure with him,” Chelsea said. “I never got a chance to say goodbye. I haven’t overcome it because I just constantly say ‘that’s behind me’ and leaving it there and leaving it in the past and not bringing it up into present day. I mean, I know he’s dead, but I don’t know that I’ve accepted it. It’s hard.”

Chelsea said that when she does try to reconnect with her father in her head that she thinks about the happy times. She thinks of presents he bought for her or times they went to the movies together.

“That’s how I reconnect and move past it, and kind of have a smile on my face after the tears are gone,” she said.

Working for the CDTF actually helps her work through the grief too, she said.

“I feel like I’m making a difference in the community,” she said, “keeping drugs off the street, and hopefully, even if it’s just one life that I’m saving, it’s going to save that person heartache in the future. So, I definitely feel like being here in a way, and I know he’s no longer alive, but I also feel like I’m kind of saving him in a way.”

Chelsea’s father was addicted to pharmaceutical pills, which is where opioid addiction starts for the majority of users. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 130 people die from an opioid overdose every day in the United States.

If you or someone you know is struggling with opioid addiction, contact the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration’s National Helpline at 1-800-662-HELP or the National Opiate Hotline at 888-784-6641.